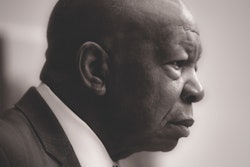

In the summer of 2020, cities, corporations, higher ed institutions and hordes of individuals around the globe declared “Black lives matter” in public statements and on protest signs and streets and sidewalks across the country. The murder of George Floyd sparked a global movement for social justice that saw a growing number of cities vote to defund police forces and reallocate their budgets to fund increased mental health and other social services. In 145 cities across 27 states, racism has been called a public health crisis and several European countries have agreed to return artifacts and control of natural resources to their former colonies. As people around the globe have begun to understand the impact of racism on the world and its systems, they have also started to work to dismantle it. Dr. Chandra Ford

Dr. Chandra Ford

But there has been a simultaneous effort to prevent people from talking about it. Notably, there is an effort by conservatives in 36 states to block any discussions of race and racism under broad attacks on the idea of critical race theory. And scholars say that while social justice and critical race theory are not synonymous, they are important components in the fight for equity — along with antiracism.

Yvette Pappoe, a visiting assistant professor of law at the University of Maryland Francis King Carey School of Law, says the media, politicians and general public seem to conflate the terms as the same.

“Anti-racism is a movement and common sense — you should be antiracist,” she says, noting that one “can be antiracist without engaging in the theory of critical race theory.” And, as Pappoe points out, “not all social justice movements are race-based.”

Critical race theory, by comparison, “is not interested in individuals and their role in racism;” instead, it interrogates the systems that uphold racism and perpetuate inequities, Pappoe says.

“If we were to try to distill out one main goal of critical race theory, it is to make apparent the ways that racism is operating in our current span of time, because so much of the way that it operates now is difficult to perceive,” says Dr. Chandra Ford, a professor in the Department of Community Health Sciences and founding director of the Center for the Study of Racism, Social Justice & Health at the University of California, Los Angeles.

But as the world tries to figure out where to start to make amends for the global effects of racism, critical race theory is an important tool to help people understand just how deep those effects run. For example, says Ford, racism has been cloaked as a series of other compounding indicators — policymakers in government and at colleges and universities have switched their focuses to socioeconomic status, or have taken to trying to solve a “diversity” problem to avoid addressing anti-Blackness directly.